by His Holiness Bhakti Vikas Swami

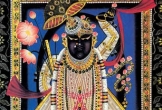

Lord Kṛṣṇa in His enchanting form as the lifter of Govardhana Hill draws thousands of pilgrims to one of India’s most popular temples.

(Published in Back to Godhead, November–December 1992)

In Kali-yuga, the present age of quarrel and hypocrisy, so many bad qualities prevail, but when we reached Nathdwara we found the quality of devotion to Kṛṣṇa still strong.

Nathdwara is in the Indian state of Rajasthan, but most of the pilgrims who come here are from the state of Gujarat, whose border lies less than a hundred kilometers away. So the mood in Nathdwara is very much influenced by the Gujaratis.

Gujaratis have gone all over India and all over the world, and they are a very successful kind of people, especially in business. Many are doctors, professors, and professionals. The Gujaratis are a cultured, sophisticated people. They are capable, modern, intelligent, “with it,” but at the same time they have their devotion to Kṛṣṇa. It’s an inseparable part of Gujarati life. So Gujaratis are sometimes said to be the most pious people in the world.

In Nathdwara we find Gujaratis not only from Gujarat but also from Mumbai (where Gujaratis form a major business community) and even overseas—Africa, England, America, and Canada.You see them everywhere in the temples and on the streets, men wearing silk kurtās and chains of tulasī and gold, and women in fine sārīs. The people have fine features.

Gujaratis are also famous for wonderful food, and this is reflected in Nathdwara. This is a holy place, but definitely not a place of austerity. Food that has first been offered to Kṛṣṇa is called prasādam, and this article could be titled “Nathdwara— Prasādam City.” Nathdwara is famous for the Deity of Śrīnāthajī and maybe just as famous for the prasādam of Śrīnāthajī. I’ll get back to that later.

“All glories to Lord Kṛṣṇa”

“All glories to Lord Kṛṣṇa”

Nathdwara is a town that lives around its Deity. It’s a small town. You’d find it hard to say what the actual population is. When you ask people they give you different ideas, but I would guess around twenty thousand, though there must be an equal or greater number of visitors. Many of the people who live here are priests, temple workers, and merchants who sell flowers, fruit, and vegetables to offer to the Deity. Then there are those who sell prasādam and pictures of the Deity, others who sell tape cassettes with devotional songs, and others who cater to the needs of pilgrims by providing hostels and hotels, buses, auto-rikshas, and so on. Nathdwara has everything a good-sized town should have, but somehow or other nearly everything is connected with the Deity.

The standard greeting here is “Jaya Śrī Kṛṣṇa!” (“All glories to Lord Kṛṣṇa!”) All about, you’ll see written the words “Jaya Śrī Kṛṣṇa!” Sometimes you’ll also see the mantra of the Vallabha sampradāya, śrī kṛṣṇa śaraṇaṁ mama (“Lord Śrī Kṛṣṇa is my shelter”). In Nathdwara the Hare Kṛṣṇa movement is well known, so often people greet us by saying “Hare Kṛṣṇa!”

The Rajasthani villagers in Nathdwara stand out brightly. They’re a lively, robust people, with their own language, their own food, and their own traditional dress. And they’re deeply devoted to Lord Śrīnāthajī.

Early in the morning, we hear a Rajasthani milk seller calling in a deep, gutsy voice, “Jaya Śrī Kṛṣṇa. Jaya Vaṁśīdhārī.” The high-powered devotion of the Rajasthanis and the gentle devotion of the Gujaratis makes an interesting contrast.

At quarter after five in the morning, a shenai band playing over loudspeakers calls everyone to the temple for maṅgala-ārati, the earlymorning greeting of the Lord. The band itself sits on the arch above the main entrance to the temple, playing musical instruments and chanting. The sound creates a spiritual atmosphere as you walk in.

Until some years ago, foreigners were not allowed into the temple, but now they are. In any case, members of the Hare Kṛṣṇa movement have always been welcome.

Getting to See the Lord

Getting to See the Lord

The ārati starts at 5:30. The temple doors open, and everyone just piles in. They may be sophisticated businessmen or whatever, but when it comes time to see the Lord it’s “get in somehow or other.”

The hall for darśana (seeing the Deity) has a series of broad steplike platforms gradually going higher toward the back, as in a sports stadium. The entrance is on one side and the exit on the other. Women enter toward the front, men toward the back.

It’s pretty rough and tumble. The temple staff at the doors and by the altar in front constantly move people on, saying, “Calo Jī!” (“Please keep moving”). The sevakas, or assistants, by the altar hang onto ropes with one hand to keep their balance and lean into the crowd, waving cloth gāmchās in the other hand to whisk people on. Everyone is moving, saying their prayers, and at the same time being pushed and shoved. But for a few seconds before you get moved on you get a very nice, close darśana of Śrīnāthajī.

The self-manifested Deity of Śrīnāthajī appeared, it is said, from a big rock on Govardhana Hill in Vṛndāvana. Physically He appears as a bas-relief, the front of His form emerging from the stone. He is dressed with cloth wrapped about Him in a stylish and pleasing manner. His dress is changed several times throughout the day. The weather here, as in most of Rajasthan, is ferociously hot in the summer, cold in the winter. So in summer He is lightly dressed, and on winter mornings at maṅgalaārati He is wrapped up so warmly you can only see His face.

Although the temple now has electric lights, torchbearers inside the temple still keep up the tradition of shedding light on the Lord with torches (thick sticks topped with cloth soaked in burning oil). When the Lord gives His darśana, beneath His lips shines a large diamond, said to be a gift from the Muslim emperor Akbar himself.

After the maṅgala-ārati, darśana goes on and on. The mukhiyajīs—as the priests here are known—close the curtain in front of the Deity, but everyone cries for more darśana. So the curtain is raised and lowered several times.

Finally the mukhiyajīs close the door, but still people clamor for more darśana, and so it is opened again. People call out names of the Lord, “Jaya Kānāiyā Lāla! Jaya Vaṁśīdhārī!” Then the door is finally closed, and a curtain made of bamboo is let down in front of it, and that’s the end.

Finally the mukhiyajīs close the door, but still people clamor for more darśana, and so it is opened again. People call out names of the Lord, “Jaya Kānāiyā Lāla! Jaya Vaṁśīdhārī!” Then the door is finally closed, and a curtain made of bamboo is let down in front of it, and that’s the end.

People at once offer obeisances and then take up brooms to sweep the temple and the adjoining courtyards. You can see that the people sweeping are not temple staff. They’re people who have taken up the work in the mood of sevā, devotional service.

The Mood of the Spiritual World

This mood of doing service for the Deity is a wonderful feature of Nathdwara. When I entered the temple yesterday, there was a big pile of chopped-up logs for use in cooking for the Deity, and people from the temple staff were telling everyone to take it inside to the kitchen. Sevā karo: “Do service!” So people were doing it. I also was fortunate enough to get a chance to help.

And there’s all sorts of service you can do. There are places you can help chop vegetables, places to make garlands, places to churn yogurt, and so on. Even people coming from rich families feel happy to do some menial service for the Deity.

Out in the courtyard people sit in circles, cutting vegetables in the early-morning sun. This groups cuts one kind of vegetable, that group another. Paṇḍitas in the courtyard sit and read from scripture.

In another courtyard a culturedlooking kīrtana group sits chanting with various instruments, but few people are there to listen, because everyone is busy bringing things for the Deity or carrying wood or doing other service.

In another courtyard a culturedlooking kīrtana group sits chanting with various instruments, but few people are there to listen, because everyone is busy bringing things for the Deity or carrying wood or doing other service.

One might ask, “There are temples of Kṛṣṇa in Mumbai, and people even have temples in their homes, so why should people come all the way here to do this service or see this Deity?” One answer is that people feel that this Deity is very special, powerful, and attractive.

Kṛṣṇa is one, but the atmosphere generated in each temple is somewhat different. Here the atmosphere is certainly wonderful. So in many ways you feel like you’re entering part of the spiritual world, where everyone is serving Kṛṣṇa. The devotees who stay here and the devotees who visit create an atmosphere of service to Kṛṣṇa: “Come serve the Lord, take darśana of the Lord, take prasādam of the Lord, and be happy in Kṛṣṇa consciousness.”

A well of Ghee

Another important part of sevā is giving things to the Lord. In front of the temple early in the morning, you can buy milk, flowers, vegetables, and fruits and bring them into the temple to offer to the Lord. People also give lots of money. The temple of Śrīnāthajī is said to be the second richest in India, after the South Indian temple of Tirupati. People also give ghee and grains. Most of the food prepared for the Deity is cooked in pure ghee.

People give ghee in cans of ten, fifteen, or twenty kilos. Sometimes a whole train car full of ghee arrives in Nathdwara. The donor often prefers to stay anonymous. The shipment is simply marked, “From Śrīnāthajī. To Śrīnāthajī.”

The temple has a literal well of ghee. Cans of ghee are cut open and slightly heated, and the ghee is poured into the well. A pipeline extends from the well to the Deity’s kitchen—ghee on tap. Ghee, of course, is expensive. But money is no bar in the worship of Śrīnāthajī.

In the grain stockroom, everything is very orderly. All the grains that come in and go out are recorded. And when it goes out it goes only to the kitchen of Śrīnāthajī. Nothing given is ever resold in the market. It’s all used in the service of the Lord.

The temple has many storerooms that pilgrims can see. One room is for keeping the Lord’s clothing and jewels. Another room, just opposite the temple, is called Śrī Kṛṣṇa Bhaṇḍār, “Śrī Kṛṣṇa’s Storeroom.” (It’s named after Kṛṣṇa Dāsa, the first manager of the temple.) This is the treasury and accounting office, and it’s where gold, pearls, saffron, and expensive clothing are kept.

There’s a room for flowers. There’s a tailoring room where clothes are sewn for the Lord. Another room holds gold and silver pots. There’s a rose room, where rosewater and rose scents are prepared. And there’s a room where books are on hand, spiritual teaching is given, and new publications are put out.

There’s a room for vegetables, a room for milk, cream, and butter, and a room for misri (rock sugar). There’s a grinding room for grinding grains (it’s still done with a big wooden mill, powered by bulls). Then there’s a room where the ingredients for the Lord’s meals are assembled before they are prepared and offered, and a room where offered food is kept just before it’s distributed.

No One Goes Hungry

The prasādam from the Deity is distributed profusely. A portion of the prasādam goes to the sevakas and temple workers, many of whom sell it. Right after the early-morning maṅgala-ārati you’ll find pūjārīs standing just outside the temple, holding steel plates bearing clay cups full of different kinds of liquid milk sweets. Later in the morning, pūjārīs go around to hotels and dharmaśālās with covered baskets full of varieties of prasādam to sell to pilgrims.

Apart from the pūjārīs, in the bazaar outside the temple you’ll find shops where you can buy prasādam, and pushcarts selling prasādam, and people sitting on the street selling prasādam.

In Caitanya-caritāmṛta we find that the Deity Gopāla, the same Deity known as Śrīnāthajī, told Mādhavendra Purī, “In My village, no one goes hungry.” Now, here in Nathdwara, where Gopāla has come, we see that this is true. Even the street dogs here are fat. I’ve traveled all over—in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Burma—and never have I seen street dogs look so well fed. Here even the dogs get plenty of prasādam—lucky dogs.

In Caitanya-caritāmṛta we find that the Deity Gopāla, the same Deity known as Śrīnāthajī, told Mādhavendra Purī, “In My village, no one goes hungry.” Now, here in Nathdwara, where Gopāla has come, we see that this is true. Even the street dogs here are fat. I’ve traveled all over—in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Burma—and never have I seen street dogs look so well fed. Here even the dogs get plenty of prasādam—lucky dogs.

Prasādam is available all through the day, and in countless varieties— different kinds at different times. After the midday rāja-bhoga offering you can get a leaf-cup full of tasty vegetables for only one rupee (less than the cost of the ingredients themselves). You can get a leaf-cup of acār (pickle), again only a rupee. There are many kinds of chutneys, fruit salads, and a unique raitā made with chopped fruit in thin yogurt spiced with mustard seeds. There are big capātīs full of ghee for two or three rupees, depending on the size. You’ll find rice, dāl, curry sauce, fried vegetables, and samosās so huge that one is practically enough for a meal.

Then there are milk sweets and sweets made with grains and sugar, rich with ghee. You can buy big blocks, made with grains, ghee, and sugar, for a hundred rupees. Some sweets include such costly ingredients as musk and saffron. People don’t haggle much over prices. Whatever the shopkeepers say, people just accept it, and that’s that.

Items like grain sweets and sugarcrusted purīs keep for months without losing freshness. A pilgrim traveling abroad from Nathdwara may bring prasādam of Śrīnāthajī to his friends overseas. Like the Deity Himself, the prasādam of Śrīnāthajī is famous all over the world.